Ad Disclosure

Breaking Barriers: A Feature Story on Phillies Interpreter Diego Ettedgui

Zack Wheeler was waiting to get loose before the start of the bottom of the sixth inning in Miami on August 2nd. The problem was, he needed a catcher to catch him.

J.T. Realmuto had cut open his hand sliding the night before and was unavailable and Garrett Stubbs was still getting his gear on in the dugout.

That’s when Diego Ettedgui stepped in.

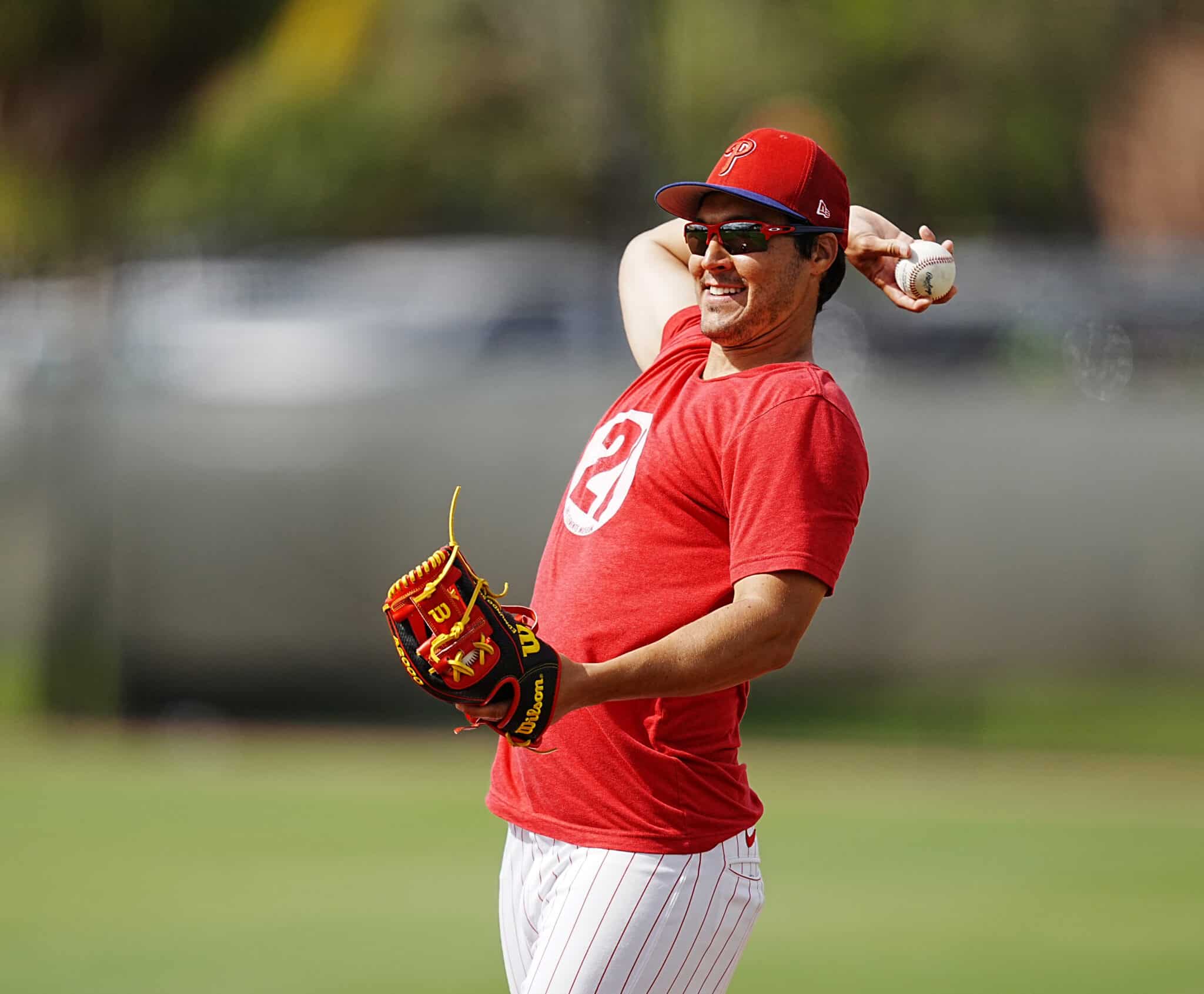

You’ve likely seen Ettedgui on your T.V. screen many times. He’s the guy who is usually translating for the native Spanish-speaking players who aren’t comfortable speaking English to the media. He’s also the guy who accompanies pitching coach Caleb Cotham out to the mound to speak to the Latino pitchers. He’s also the guy who takes care of the PitchCom equipment, and sometimes has to run a new transmitter out to the pitcher when the batteries go bad.

But catching Wheeler? This was a new adventure.

Ettedgui has caught pitchers before – he is especially close with Ranger Suarez and often plays catch with him in the outfield – but Wheeler throws 97 MPH. For a guy who was a soccer player in college and didn’t play baseball, this was going to be a whole new experience.

But, as he does with every challenge that has emerged in front of him in his life, Ettedgui tackled it head on. He was going to do the job until Stubbs was ready. “He better be ready soon,” Ettedgui thought to himself, but he wasn’t going to show any signs of nervousness.

He popped into the old-school crouch behind the plate, as opposed to the one-knee stance most catchers use today, and he was ready. The first pitch from Wheeler came in.

WHAP!

The sound was the loudest Ettedgui had ever heard a ball hit a glove. But he caught it. He was proud of himself and threw it back. Then came another pitch.

WHAP!

And another.

WHAP!

Photos courtesy of Miles Kennedy/Philadelphia Phillies

By the fourth pitch, the T.V. broadcast was back live and play-by-play announcer Tom McCarthy pointed out that Ettedgui was filling in for Realmuto. The camera tuned in as Wheeler lobbed a pitch that barely made it 60 feet six inches that caught Ettedgui a little by surprise and he sort of fell forward to catch it. When he went to throw the ball back, Wheeler waved him off. McCarthy had a good chuckle about it, assuming Wheeler just didn’t want to throw the ball to Ettedgui behind the plate. But that wasn’t really the case.

“I just didn’t want to throw any more pitches,” Wheeler said. “It was going to be my last inning and I didn’t want to waste whatever I had left in warm up. I was good to go. It had nothing to do with Diego.”

Wheeler said no pitcher throws their real fastball in warmups. He said he probably throws high 80’s usually. And the first pitch he threw Ettedgui was at that speed, but then he ramped them down even a little more after that, because he didn’t want to hurt Diego.

“Well, he caught the first one almost behind his head,” Wheeler joked. “So, I had to take it easy on him after that.”

It was a funny moment. When Ettedgui was told about what Wheeler said, he nearly doubled over with laughter. Six years ago though, this would never have happened. Because Ettedgui would have been nowhere near the dugout during the game. And eight years ago, A role like Ettedgui’s didn’t even exist.

An MLB Mandate

In a game in Boston in 2014, Yankees starter Michael Pineda was tossed from a game at Fenway Park after Red Sox manager John Farrell had asked home plate umpire Gerry Davis to check Pineda for an illegal substance. He obviously had pine tar on his neck and was going to it frequently with his throwing hand before throwing pitches.

There was a question about him using pine tar against Boston in his previous start against them, and this time the Red Sox were looking for it.

There has been a lot of speculation about how the Yankees communicated with Pineda by then-manager Joe Girardi and GM Brian Cashman. The Yankees insist they told Pineda after the first Red Sox game that pine tar was illegal, but they would not say (and still never have said) whether it was communicated to him in English or in Spanish.

Pineda eschewed English classes while he was with his original team, the Seattle Mariners, choosing to stick to a small circle of Spanish speaking teammates, but once he got to New York, and the crush of baseball media that surrounds the Yankees, Pineda was prideful and wanted to try to answer questions in English, and started working on speaking in English during media sessions.

However, there were still English words he did not understand. There were still questions that were being asked at a more rapid speed, making it hard for him to completely get the crux of the question being posed to him.

So, on that fateful night in Boston, when he was made available to the media, Pineda struggled to find the right words, and repeated himself frequently. The New York media were relentless in their questions. Asking the same questions a few times. Pineda was obviously uncomfortable in the interview, and it’s obvious a few times he didn’t understand the question being asked.

Watching Pineda suffer through this interview, teammate Carlos Beltran had seen enough. He started advocating for Latin0 players to have an interpreter to help them, not just with interviews with the media, but with everyday communication in an English-speaking world.

He kept pushing and pushing and pushing, and finally, in January of 2016, MLB issued a league-wide mandate that each team needed to employ a Spanish-speaking interpreter.

The league would provide each team with $65,000 to hire one for the 2016 season and each season going forward.

While coaches and fellow players had often served as ad hoc interpreters for native Spanish-speaking players, they were not trained on how to be interpreters and it sometimes led to confusion or mistakes.

Players who come from Asian countries almost always have interpreters included in their contracts, however Asian-born players made up just 1.3% of Opening Day rosters in 2023.

Athletes born in Latin American countries, on the other hand, made up 25% of the league.

“Every Latino that plays at the MLB level wants to learn English and get better, but it takes time to pick up the language, and it doesn’t happen overnight.” Beltran told MLB.com at the time the league mandate was announced. “I do believe once Latinos get to a point where they feel they can do an interview in English, that some won’t need an interpreter anymore. But others will, and this is something that was needed and overdue.”

“Don’t Come Home”

Ettedgui, 36, was born in Venezuela. His parents, Carlos and Maria, were always instilling in him and his younger sister Anna to never stop striving to be the best at whatever job they had.

“My mom used to say, ‘If you are selling ice cream, then be the best person scooping the ice cream,'” Ettedgui said. “‘If you are playing soccer, then be the best soccer player on the team.’ My dad was that way too, but he was a little more direct. He would say, ‘You aren’t going to inherit a lot of money from me, but I am going to make sure you get the best education possible, so that you can climb the ladder in whatever you do and be a success.'”

When it was time for Diego to hold his dad to his word, he had a difficult choice. Should he just go to college in Venezuela? Or should he go to America and learn to speak English first?

He decided that learning English was more important. So, he flew to Boston to enroll in an intensive, six-month course.

Why Boston?

“My mom asked me where I wanted to go and I didn’t know,” Diego said. “She had a few friends who told her that they had been to Boston and that it was nice, so that’s where we went. I didn’t know anything about Boston. I mean, I didn’t know it got cold there until I was there.”

Three weeks before the end of his class, as Diego was studying for the final exam and thinking about heading back home once it was done, he got a terrifying phone call from his dad.

His grandfather had been kidnapped in Venezuela.

According to Diego, this was very common thing. He called it “express kidnapping.”

“They would kidnap you in the morning and hold you for ransom,” Diego said. “If they didn’t get the money later that day they would either let you go, because they didn’t have the guts to kill you, or they would just kill you. You are at their mercy. My dad was the one who paid the money. He had to drop it off in a random location.”

And then pray.

Carlos called his son that night to tell him that his grandfather was released.

But just as Diego was feeling a sense of relief, Carlos said something else that was completely unexpected.

“Diego, do whatever you can to stay there,” he said. “Don’t come home. It’s for your safety.”

At just 18-years-old, and with just six months of English training, Diego had to make it on his own in another country, far from home.

In high school, Diego was an athlete. He played a little bit of baseball, but his best sport was easily soccer. Not knowing where to start, he reached out to the soccer coach at Bunker Hill Community College in Boston.

He thought maybe he could get a scholarship. But community colleges don’t hand out scholarships like Division I programs. However, the coach said he might be able to help a little bit – if Ettedgui could prove he could play at that level.

So, Diego went out onto the pitch for the Bulldogs coaching staff, and right after his workout, he was told that they could get him a discounted rate to attend. He would pay in-state tuition even though he was an international student.

While at Bunker Hill, Diego majored in international business, and got an associate degree. But getting a business degree in 2008, in the midst of the country’s financial crisis, didn’t seem like a safe path, especially for a Venezuelan national.

He decided to stay in school.

Diego then enrolled at Northeastern University, where one of his academic advisors suggested switching into healthcare management. No matter how bad things were with the banks and the economy, people were always going to need healthcare, so this seemed like a more stable industry.

It wore him down.

He started by working for an insurance company in Boston called The Health Connector. His job was to try to get people to understand and enroll in Obamacare. His patience with that process lasted all of six months.

He next went and tried his hand at the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center. After six more months there, Diego started asking his bosses if there was a path to improving his job status within the company. From their responses, he wasn’t given much hope for the future. Each night, after work, he went back to his apartment, dejected.

A Motivational Commercial

Not happy in his career, and not knowing what the future would hold, Ettedgui popped on the television to try and lose himself in some mindless entertainment.

One night, he saw a commercial. He was both tired and frustrated, so he doesn’t remember exactly what it was a commercial for, but one singular message came across:

If you pursue what you love, you will never work again.

“I started thinking when I saw it about what I loved,” Ettedgui said. “And it wasn’t business, and it wasn’t healthcare. It was sports. And the more I thought about it, the more I realized that I had no responsibilities to anyone except myself, so why not pursue that passion? Why not see if I couldn’t find a career in sports?”

The next day, during his lunch break at the Health Center, he was reading the newspaper, and saw an advertisement for a communications course. He decided to enroll in it.

“It was the best decision I ever made in my life,” Ettedgui said.

Ettedgui immersed himself in the course. So much so, that he really caught the attention of his Colombian-born professor, Carlos Quintero. Quintero pulled him aside after class one day and suggested that Ettedgui pursue a career in the media. In fact, Quintero was so sure Diego would succeed, that he got him not one, but two jobs – one as a general assignment sports reporter for a Spanish-language newspaper in Boston, and a second hosting a five-minute sports update segment on Quintero’s own local Spanish radio program.

Quintero used to buy time on 1600 AM, WUNR Radio International in Boston. The newspaper, El Mundo Boston, was sending Ettedgui to cover the Celtics, the Red Sox and the New England Revolution.

He would do interviews and write about them in the newspaper, and then play the audio of the same interviews on Quintero’s show.

One day, while Ettedgui was doing his sports segment on Quintero’s program, the next host, an El Salvadorian woman named Juanita Benitez, who centered her show around playing Mexican music, came into the studio early and saw Diego give his update.

She had been looking for something to spice up her program, and although her show didn’t have a sports element at the time, she liked his exuberance and the way he sounded. So, she approached him.

“Her show was two hours long, and she was thinking about adding a co-host,” Ettedgui said. “She said she would pay me to be her co-host and we would play music, talk, and I would still do my sports update.”

So, Ettedgui joined Benitez for her program.

The guy who sold the radio time to both Quintero and Benitez was named Daniel Gutierrez. Aside from selling radio time, Gutierrez also hosted a daily television talk show called “Ritmo Guanaco” on MasTV, a small studio located in the Boston suburb of Sommerville. He showed up at WUNR one day to collect from Benitez and heard Ettedgui’s sports update. He asked Diego if he had ever done television work.

“I told him no, but that I would be interested in giving it a shot,” Ettedgui said.

Gutierrez made him a deal.

“Next week we’re going to have a segment on Olympic soccer,” he said. “Come into the studio and we’ll give you a shot and see how you do.”

Diego agreed. He showed up and was included for the final five minutes of a half hour show.

Gutierrez liked Ettedgui and asked him to come back the following week. So, Diego did. Another five-minute segment. Another invite back for a third week.

Then something crazy happened.

Right place, right time

When Ettedgui got to the studio, he was shocked to learn that Gutierrez got into an intense argument with one of his co-hosts and walked out. Not just for the episode. Forever. He quit. On the spot.

Desperate for a new host to take over for Gutierrez, the station looked at Ettedgui and offered him the position.

He had done two five-minute segments and now he was going to be a regular host.

Javier Marin, who owned the station, was so impressed with Diego’s ability to just jump right in on such short notice and with such little experience, that he offered him his own show titled “Lucky y el Monstruo Verde” (Lucky and the Green Monster). It was a show focused solely on the Celtics and Red Sox.

It was so successful that he was later added to the broadcast of “Totally Patriots,” which was a football show for kids.

“It was a show in English that was part of (Robert) Kraft Productions,” Ettedgui said. “Marin had a connection with them, and they let us put it out in Spanish. It was a half hour show, but it took four hours to do all the translating, and then I had to record the voice over on top of that. It was a lot of work for a half hour show, but I loved it.”

While doing his work covering the Red Sox, Ettedgui became friendly with an MLB employee and ended up making a connection to start doing work for MLB.com, translating news stories from English to Spanish. Then, he heard about the MLB mandate for interpreters and decided to apply for the Red Sox position.

After all, he had all the tools that were listed in the job description – be bi-lingual, familiar with MLB players and baseball terminology and be exposed to speaking on camera and in front of a group of people.

He filled out the online form and got a call from Kevin Gregg. Gregg, now the Vice President of Baseball Communications for the Phillies, was in a similar role with the Red Sox in 2016. Gregg interviewed Diego and was really interested in hiring him with the Red Sox but was considering a few finalists for the position.

While waiting to hear from the Red Sox, Ettedgui got a call from Greg Casterioto, who was the Director of Baseball Communications at the time for the Phillies.

He had seen Diego’s application online and wanted to interview him. Ettedgui set up a Skype call with Casterioto and his communications team, and after the initial interview, Casterioto called him back and said they wanted to give him a trial run at Phillies Spring Training for four days.

Ettedgui was in a tough spot. He had all of his various media jobs and he was also coaching soccer with three different programs in the Boston area. He was the assistant coach at Bunker Hill, where they had just come off of an appearance in the NJCAA National Championship Game, but he was also the head coach at a Boston elementary school as well as with America Scores, a soccer program designed to teach the sport to inner-city youth.

“I had five jobs and no health insurance, so it wasn’t an easy decision to just up and fly to Florida for four days,” Ettedgui said. “But then I remembered the commercial that got me started on this path, so I took the chance.”

In February of 2016, the Phillies flew Ettedgui from Boston to Clearwater. Seeing how he interacted with the Latino players, it didn’t take the Phillies long to realize they had their guy.

On Day 3, Casterioto offered Diego the job.

“I wanted to say yes right away, but I felt I owed it to Kevin and the Red Sox to call them and tell them what was going on, so I asked Greg if I could have a day and then let him know,” Ettedgui said. “I called Kevin that night, and he wished me well and told me I would love working for the Phillies.”

Eight years later, he knows Gregg was right.

Diego, the Advocate

When the Phillies acquired Cristian Pache in April, it was an interesting transaction. Pache had already shown elite defensive skills in the outfield in his time in the majors with the Braves and the A’s, but at no time was there an inkling that he could ever hit at the big-league level.

Once he got an opportunity to play for the Phillies, albeit mostly against lefties, and a small sample size derailed by a few injuries, Pache actually started to show signs of being able to hit the ball with authority.

After one game, Pache credited the fact that the Phillies let Ettedgui sit in on his batting cage sessions with hitting coach Kevin Long as one of the reasons he was able to make the adjustments that the Phillies wanted him to make.

He said he’d never had that before. It was a little surprising to hear that, especially with the Braves, who run a first-class baseball organization, but Pache was effusive in his praise for Diego and how it had helped him once he got to Philadelphia.

“Hitters like Pache, (Edmundo) Sosa, even Odubel (Herrera) last year – they speak English,” Ettedgui said. “And the coaches do a good job of understanding that English is a second language and try to speak as simply as they can, but sometimes the players still don’t understand, and that’s where I come in. Yesterday we were talking to Sosa about some stats. They were analytics. Having me there to translate made it easier for him to understand.”

And that’s the thing. Ettedgui’s role has developed over his eight years with the Phillies. Not only is he used as a translator for the players during media interviews, but now he sits in with the Latino players on bullpens and side sessions, or in the cages, or in meetings with the manager and coaches, and he’s able to make them feel more comfortable that they’ll understand the message more clearly – unlike what happened with Pineda and the Yankees back in 2014.

“When I came on board it was pretty apparent right away just how much energy and positivity he has and how charismatic he is and how he’s always willing to help in any way,” said Phillies general manager Sam Fuld. “Independent of anyone’s official role, if you have someone who is willing to help out in various capacities, you are foolish to not take advantage of that.

“The language barrier is thicker than we care to realize sometimes. We take for granted that even if somebody’s first language isn’t English, they still fully comprehend what is being said. Whether it’s breaking down the intricacies of a pitcher’s delivery or a batter’s swing, or advanced scouting, there’s a lot of communication on a daily basis that we just assume gets ingested.”

Fuld continued, “To have someone there to make sure that nothing slips through the cracks is invaluable. If you think about it, if you have a conversation between an English-speaking coach and an English-speaking player and every fifth word were cut out, that wouldn’t be optimal. We have a lot of Latin American players who have done a great job improving their English, but that doesn’t mean that it’s easy.”

And Ettedgui has been integral to the lives of many of those Latino players in the last eight seasons, especially the guys currently on the roster.

When his role was evolving, Ettedgui moved from Newtown Square in Delco down to South Philly and lives close enough to Citizens Bank Park that he often will walk to work or ride his bike when there is good weather. This allowed him to be closer to the players, most of whom live in the city, so he can assist them in whatever they need outside of baseball.

“He does everything for us,” said Seranthony Dominguez. “You can call him at any time of the day or night, and he will answer the phone and help you. I remember one time I was in the Dominican Republic, and I called him at 4 a.m. because I was having a problem with my flight. He’s not supposed to have anything to do with that, but he answered the phone and helped me anyway. He does this for anybody in here.”

Dominguez’s English is very good, considering it’s not his native language, but even he gets tripped up sometimes, and having Ettedgui there to lean on adds a layer of comfort that didn’t exist for Latino players prior to 2016.

“I understand about 80 percent of what you guys ask, and most of the time it’s easy to answer, but if there’s a word I don’t know, I can just ask him and it makes it easier to give the right answer,” Dominguez said. “And sometimes, I want to say something in English, and I don’t know the word, so I ask Diego and he tells me, and so I learn some new English from him too.”

If players need to make arrangements for family or friends coming into town to visit, Diego is there. If players need advice on where to live in Philly or need to understand the legal language in their leases, Diego is there.

“I thought I would be just an interpreter,” Ettedgui said. “Year after year I realize more and more that translating is becoming a lesser responsibility. It’s still my primary job, but now I go to doctor’s appointments for scans and MRIs. I’ve gone to car dealerships with guys to buy cars. I’ve gone house hunting with guys. I’ve helped guys pay utility bills or refill their cell phone plans. I’ve filled out paperwork for rental agreements. I throw with Ranger every day. He wants to throw with me, every day. I’ve done flat grounds with Yunior Marte and (Gregory) Soto. I didn’t have to do it, but I wanted to learn and help.”

Like his mom said, “If you’re selling ice cream, be the best at scooping ice cream…”

‘Say yes to Everything.’

When Joe Girardi was fired and Rob Thomson was named interim manager, Girardi’s coaching assistant Bobby Meacham was also let go.

Meacham had two in-game responsibilities while with the Phillies. He was in charge of the managing the PitchCom system and he was responsible for throwing the first baseman a warm-up ball as they were coming off the field between innings, so the first baseman would have one in his glove for the next inning.

One is a little more important than the other, but it’s also evidence as to how every little detail to a ball game is pre-planned and how many people have super-specific responsibilities.

When Thomson was named the interim manager, Ettedgui popped into his office to congratulate him. In the process, Ettedgui told Thomson that if there was anything he can do to help out, he would. Thomson asked Diego if there was anything he thought he could help with right away. Ettedgui mentioned Meacham’s responsibilities. Thomson didn’t even think twice. He knew Diego would embrace both jobs. He said yes immediately.

“Everyone always wants more responsibilities to prove you are part of the team,” Ettedgui said. “You are here to help them win games. I want to do that any way I can.”

Ettedgui said that although he manages the actual PitchCom transmitters and receivers, his responsibilities are simply to make sure the batteries are charged and to make sure the voice settings are correct for pitchers who want to hear them in English and those who want to hear them in Spanish. Additionally, he makes sure that the centerfielder, shortstop, second baseman, and starting pitcher and catcher have theirs, and then he ensures that four are sent out to the bullpen. He then keeps the three spares handy in the dugout in case one of the ones in use craps out.

“The PitchCom guru is really (Senior Coordinator of Major League Pitching Strategy and Analysis) Shaun Rubin,” Ettedgui said.

Rubin, a former pitcher for Harvard University, helps pitching coach Caleb Cotham with reports and heat maps and the like.

“We basically team up, Ettedgui said. “He configures all the software, but (baseball rules do not) allow him to be in the dugout. So, I handle all the stuff with the PitchCom in-game.”

And then there are the times he warms up pitchers between innings, even if catching a Wheeler fastball is not the easiest thing to do.

“My grandparents used to tell me to always say yes to everything,” Ettedgui said. “Grow. Absorb. I like helping out. If I can help the team with little things, it’s a win/win for everyone. I don’t just like sitting around.”

The thing is, the first two years he was in Philadelphia, that’s all he did. When MLB mandated the hiring of Spanish-language interpreters, there was no job description other than requiring they be there for pre- and postgame media interviews.

So Ettedgui would arrive at the ballpark for the one hour the clubhouse was open to the media before the game – in case there were requests to speak to Latino players who required a translator – then he would be banished to the press box until postgame, when he would go back into the clubhouse for potential game-related interviews.

That was it. There was a substantial amount of down time.

But one person changed all that, and it’s made all the difference – not just for Ettedgui, but for every Latino player that has donned a Phillies uniform since 2018.

‘This was a necessity.’

At the start of the 2018 season, the Phillies had a new manager. He was different. He was unorthodox. Ultimately, he wasn’t for Philly. But one thing you could never say about Gabe Kapler is he didn’t care about the people around him.

Kapler is well known as someone who wants to get to know everyone he possibly can in an organization. He believes that the more you know about someone, the more you can figure out ways they can help your team succeed.

So it was no surprise that after just the first few days of his first Spring Training with the Phillies, Kapler had noticed how close Ettedgui was with the Phillies Latino players. He called Diego into his office and got to know him even more. It was then that Kapler sprung an idea on Ettedgui – how would he like to be in the dugout, in uniform, during the game?

From Kapler’s perspective, this would allow for improved communication between the coaches and the players if Ettedgui were there to be able to translate for both sides.

Ettedgui was immediately on board with Kapler’s idea, and the Phillies manager went to Casterioto and told him that Diego would be more beneficial to the ball club if he were in the dugout during the game than if he were sitting in the press box.

Kapler got his wish, and eventually let Ettedgui do more than just translate.

“Gabe gave him the freedom to help in various ways,” Fuld said. “Even if it was shagging fly balls in batting practice or developing relationships with called-up players or just being around for anything any of the players or coaches needed. That was really cool. It energized Diego and to this day, it continues to help us in so many ways.”

When Kapler was in town last week with his current team, the San Francisco Giants, he had a very busy schedule. But when he found out that he had an opportunity to not just talk about Ettedgui, but to also talk about the needs of native Spanish-speaking players in the game today, he made sure to carve out some time.

Bill Streicher, USA Today Sports

“Native Spanish-speaking players are at a pretty significant disadvantage in baseball,” Kapler said. “They’re unquestionably in the minority at the major league level, in terms of numbers, in almost every situation. Meetings. Conversations. Analytics packages. Strategy discussions. All of those are incubated and designed in English. They are, often times, shared in English exclusively. Sometimes (there is) a translator, but not always all that thoughtfully. Diego had a very good relationship with me and our English-speaking coaches and had a very good relationship with our Spanish-speaking coaches and our Spanish-speaking players. I trusted, and it sounds like the Phillies are continuing to trust, that this guy is not a one-dimensional human who can make one language become another. A really good translator takes the energy of the conversation and translates that, rather than a word-for-word translation, which, in a lot of ways, is not important.”

In other words, he’s a lifeline for the players if they seem to be struggling to answer the question, even if they are trying to answer in Spanish.

While some viewed this as Kapler just trying to be different and having more people in the dugout than were necessary, he was absolutely being innovative, and making an effort to improve his team in ways that were more outside the box.

“This was not a gift for Diego,” Kapler said. “This was a necessity for native Spanish-speaking players who don’t get the advantages that native English-speaking players get. I believe that emphatically.”

Kapler also praised Ettedgui as being someone who wasn’t afraid to communicate to the coaching staff if a player felt out of the loop or if they felt like they weren’t understanding the message being delivered to the team as a whole.

“One of the things I’ve seen in baseball for many years, and one of the reasons I’m very happy to have this conversation, is that in Spring Training, meetings are had in English. If there’s a 15-minute meeting in English, it’s not uncommon to see native Spanish-speakers not get anything out of it, and just kind of sitting through it,” Kapler said.

He added that since his time in Philadelphia, he has instituted a practice where sometimes meetings are done in Spanish first, just to give the English-speaking players an understanding of what the Latino players are experiencing. Kapler had first-hand experience with this when he played in Japan and faced the challenge of a language barrier himself, even when he had a translator available to him.

“So much gets lost in translation,” Kapler said. “There’s so much nuance. There are so many layers to the emotions of Major League Baseball players that you need people around that can bridge that gap and Diego is one of those people.”

Ettedgui recognizes that he wouldn’t be where he is today, were it not for Kapler.

“I owe him. I owe him big time,” Ettedgui said. “It made a big difference. I feel like I’m wanted. It helped me to have a better relationship with the players. They like it. They see that you are always there for them, good or bad. It was easier for me to show them that once I was in the dugout.”

‘We’re not there yet.’

When the Phillies clinched the National League pennant last October, Ettedgui was celebrating with the rest of the team. At one point, Rhys Hoskins walked over to him and told him how important he and other support staff are to the team’s success.

“He said, ‘I have to thank all you guys because all we players have to do is worry about what’s taking place on the field because you guys are taking care of everything behind the scenes,'” Ettedgui said.

It made Ettedgui proud. It made him feel like all the work he had done, all the hustling with multiple jobs and constantly trying to get noticed by his superiors, was all worth it.

It made it sweeter for Ettedgui, who is one of just four of the interpreters who were originally hired under that 2016 mandate who are still working in MLB.

There’s a lot of attrition because of the vagueness of the job description. Some teams take advantage of their interpreters, not paying them more than what MLB provides. Others make their interpreters punch a time clock, and don’t treat them as salaried employees, which is rough considering all of the travel commitments and off-the-field assistance that can’t be measured simply by the hours spent in the ballpark.

There is a group chat among all 30 interpreters. They share their successes with one another as often as they share their gripes.

But Ettedgui doing as much as he is doing, and always saying yes and being the best he can be, has made people take notice. And by being given the freedom to continue to grow in responsibility with the Phillies, from Kapler to Girardi and now with Thomson, it’s starting to make people realize the value of the position, and not that it’s just something the MLB instituted to make carping by the likes of Beltran go away.

“What we have done collectively is add value to our position across the league,” Ettedgui said. “I know I’m going to work, but I don’t feel like I’m working. I’m passionate about what I do. I know I’m making a difference in these guys’ lives.”

Kapler said it was the right thing to do, and that MLB is making strides when it comes to eliminating language barriers but said there’s still meat on the bone.

Take for example, “Something as simple as a native Spanish-speaking player at the plate, trying to communicate with an umpire with the new rules,” Kapler said. “Our English-speaking players and our staff barely understand the rules. Now, if you are a native Spanish-speaking player and you get a strike called on you and you don’t understand why, you have nowhere to turn. The interpreter is in the dugout. It takes a pretty big, bold personality to call for the interpreter just to talk to the umpire. Talk about a major disadvantage. It’s huge.

“We’re working through it as an industry. Major League Baseball is doing a lot of good work, but we’re not there yet.”

As the innovator of this idea to bring Ettedgui into the dugout and make him, and others in his role, more a part of the process, Kapler was pretty adamant about what needs to happen next.

“Lots of conversations like the one we are having,” he said. “Getting it out there. Talking about it. Acknowledging that our native Spanish-speakers are at a disadvantage, and we need to do things as an industry to level the playing field.”

Circling back

Diego Ettedgui doesn’t know how long he plans to be an interpreter for the Phillies. Right now his focus is on doing everything he can to help them win a World Series.

But he does recognize that he’s built quite a resume. In March, he left Phillies Spring Training for a short time to work as a translator for the umpires working the World Baseball Classic. Free from the threat of express kidnappings, his parents and his sister now live full-time in Miami. Diego has a place in Miami as well.

“The Phillies organization is very family oriented,” Ettedgui said. “They let me work from home in the offseason so I can spend time with family. I have a 5 -year-old niece and a 2-year-old nephew – Alesia and Alejandro. They bring so much joy to my life. They are like my own kids. So much so that I got their names stitched on my glove that I use out on the field.”

All of this has happened for Diego because he made a decision to follow the advice he saw one night on a commercial, and because he chose to listen to his grandparents and his parents. And yes, mom, he’s the best at scooping the ice cream.

Anthony SanFilippo writes about the Phillies and Flyers for Crossing Broad and hosts a pair of related podcasts (Crossed Up and Snow the Goalie). A part of the Philadelphia sports media for a quarter century, Anthony also dabbles in acting, directing, teaching, and strategic marketing, which is why he has no time to do anything, but does it anyway. Follow him on Twitter @AntSanPhilly.