Ad Disclosure

Robert Covington Was a Good Player, End of Story

I hope Robert Covington and Dario Saric get a roaring round of applause from Sixers fans when they return to Philadelphia as Timberwolves on Tuesday, January 15th.

That should be the bare minimum for a pair of starters from last year’s 52-win playoff team, a squad that finished in the top four of the Eastern Conference for the first time since the 2002-2003 season.

Covington is a unique case, one of the strangest stories I’ve encountered in nine years of working in Philly sports.

Here’s a guy who was undrafted out of Tennessee State, came through the D-League, earned a spot on an NBA roster, and wound up signing a multi-million dollar contract as a 3 and D utility man on a playoff squad. Nine times out of ten, Philadelphia would lap up that kind of underdog story and throw unconditional support behind a player who really worked his ass off to make his dreams come true.

Yet Covington really didn’t receive that type of support from the greater Philadelphia sports community, probably because he was the product of a divisive rebuild which saw a large majority of fans completely tune out the Sixers from 2013 until maybe halfway through the 2016-2017 season.

During that time period, fervent Sam Hinkie supporters were all-in on the Process, watching every single minute of guys like Nerlens Noel, Jahlil Okafor, and Jerami Grant while the other 95% of Philadelphia didn’t really give a shit. They just wanted someone to wake them up when the Sixers were good again.

There was always an obvious generational split between younger fans who appreciated the pragmatic approach to tearing down a team that hadn’t achieved diddly poo in 10+ years, vs. an older section of fans (and media) who fundamentally disagreed with the concept of losing on purpose. That dichotomy still exists today via useless arguments over who was right and who was wrong, as if it really fucking matters.

The relevance to Covington is that a vast majority of Sixers fans who came back around last year simply did not watch or understand the developmental years that turned RoCo into a viable swingman on a bona fide playoff squad.

So that’s one thing. People just weren’t watching back then, or they held everything “Process” in contempt, so there’s a natural distrust or disbelief in any player that came through that era based on a general feeling of antipathy towards the entire exercise in general.

Likewise, I PERSONALLY BELIEVE that there also exists an “overcorrection” on the other side of the spectrum, which I’ve written about ad nauseam. The most cultish of Sam Hinkie supporters continually hammered home the idea that Covington was among the NBA’s defensive elite, a wonderful player whose “diamond in the rough” development justified the decision to tank. He made appearances on the live Rights to Ricky Sanchez podcast and came to the wedding that took place at Xfinity Live earlier this year. “Rock” Covington was a favorite among Hinkie types who lived and breathed Sixers when they were posting 10 wins and 72 losses, and because he was one of their favorites, casual Sixers fans who dislike Process-supporters also disliked Covington by extension.

RoCo just falls into that gaping chasm between each end of the Sixers fan spectrum. Process types love and defend him as a Hinkie treasure and developmental success story. Covington’s ascendancy helps justify their opinion that all of this shit was worth it. Non-Process types who didn’t watch him play until 2017 think he’s overrated and gets an unreasonable and frothy push from the Hinkie supporters.

It’s kind of like a goofy sporting version of the chicken and egg, isn’t it? Which came first? The RoCo love or RoCo hate?

The other thing is Covington’s skill-set, which I would describe as “optically challenging.” You have all these people coming back on the bandwagon who can easily identify a stone cold shooting night and lackluster 1v1 defending, but they can’t identify a key switch, a well-guarded pick and roll, or overall defensive utility during the run of play.

No, Covington does not defend well in 1v1 on-ball situations. He’s not Patrick Beverly. He’s not a pesky lockdown defender.

He’s a flexible utility man who is capable of switching two through four, stepping up to handle smaller shooting guards and sliding down to handle bigger power forwards in the same possession. He’s a glue guy, a swingman, a utility knife, a prototypical modern day “3 and D” NBA player.

Statistically, this is Covington as a “3 and D” guy:

- 41 deflections is second in the NBA this year

- 1.8 steals per game is tied for 7th

- 1.8 blocks per game is double last year’s average

- +1 net rating, third on the Sixers behind Joel Embiid and JJ Redick

- 39% from three is a better percentage than Redick, Landry Shamet, Dario Saric, and any other qualified Sixer. It’s also better than Kyle Korver, Jayson Tatum, Kemba Walker, and a bunch of other high-profile NBA shooters.

Covington also finished last year with 200 three pointers, 70 blocks, and 130 steals. Those are the parameters you’re looking for in this type of player. This is exactly what “3 and D” means. You defend, swipe some balls, get your hands in passing lanes, make some switches, and contribute catch and shoot three-point shots on the other end of the floor.

It’s true Cov was streaky, for sure. He had a horrible playoff series against the Celtics and shot 25% from deep while putting up a 0-6 shooting mark in game one and a 0-8 shooting mark in game three. He finished with a much more respectable 37.5 three-point percentage in the Miami series while averaging 9 points, 6 rebounds, and 5 assists.

That’s what he is. He’s a role player, isn’t he? If you were expecting Robert Covington to put up 22, 10, and 7, you were looking at him the wrong way. He was a glue guy on a team with two superstars and a veteran shooting guard. I think some of the folks that came back on the bandwagon last year expected him to be some elite two-way player in the Paul George and, well, Jimmy Butler mold, but RoCo, isn’t that, which is why they packaged him in a deal to get one of the two guys I just mentioned.

Going back to the “optically challenging” thing, I just think it was harder for the casual fan to identify what he did do well.

On a clip like the one below, it looks like he’s scrambling to defend Tyler Johnson here, but that’s not really the case:

Watch Ersan Ilyasova on that play and you’ll see he starts off in the wrong spot. Stuck in a 2v1 situation, Covington does a nice job of going over the top of two screens to deny an open three pointer, and Johnson eventually settles for a long-range two instead. You’ll take that type of shot any day of the week.

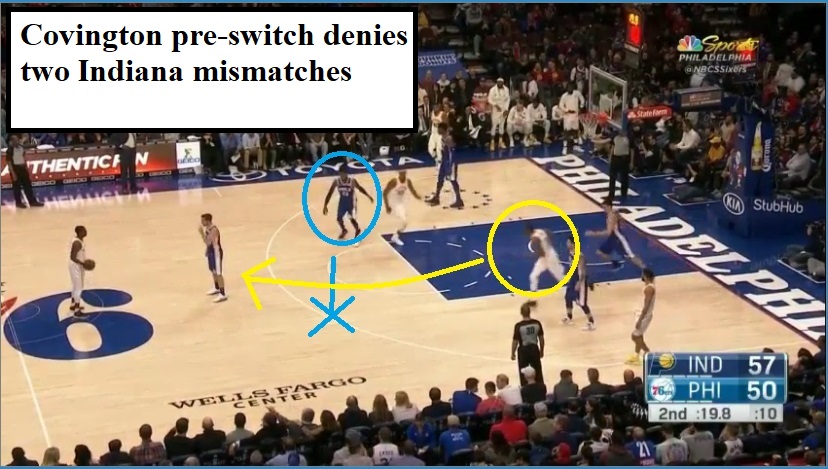

In this clip below, you see Cov’s defensive IQ on display as Indiana tries to get Joel Embiid in a switch on the perimeter:

Covington executes what’s called a “pre-switch” here, as he follows Myles Turner to the perimeter instead to prevent Embiid from getting switched onto a smaller player. Eventually Darren Collison just drives to the rim and gets stuffed.

And Cov actually does this twice in the same possession, once on the Turner screen and then again when Indy audibles to Thad Young instead:

Those are two examples of things that I don’t think the casual fan is necessarily picking out during the course of a game. It’s much easier to identify when Covington bricks a bunch of three pointers or has trouble finishing a contested layup at the rim.

Again, the framing is important here. Robert Covington was a glue guy. He was a utility knife small forward who came through the D-League and had the opportunity to develop his game in a unique situation. Back then (and even now), non-tanking teams just were not/are not finding significant developmental minutes for a fringe player who was not drafted. Rob earned his money by working his ass off to improve his game and evolve into a viable 3 and D NBA player. And his manageable contract allowed Elton Brand to package him in a deal that landed an elite two-way player. They took a guy off the scrap heap, turned him into a good player, and used that value to swing a deal for a top-20 NBA guy.

Covington is a wonderful success story that didn’t get a ton of play in Philadelphia, and I 100% believe the reason for that is because the nature of the Process fractured the Sixers’ fan base into pro-Hinkie and anti-Hinkie crowds, which I think resulted in a lot of people simultaneously overvaluing AND undervaluing Covington. You see similar things with T.J. McConnell, don’t you? Half the fan base loves his heart and hustle while the other half doesn’t even think he belongs on the floor.

Like most things, the truth is probably somewhere is in the middle. Robert Covington was not an elite two-way NBA player, but he was a very good utility man who certainly earned his money here. He was a great dude, to boot, and was always solid with fans and media. I’m very interested to see how he does with Minnesota and how those fans receive him.

Kevin has been writing about Philadelphia sports since 2009. He spent seven years in the CBS 3 sports department and started with the Union during the team's 2010 inaugural season. He went to the academic powerhouses of Boyertown High School and West Virginia University. email - k.kinkead@sportradar.com