Ad Disclosure

Iso Embiid? It’s Actually Not a Horrible Closing Strategy

It’s often thought that the best way to close NBA games is to give the ball to your best player and have everybody else get out of the way.

Normally that player is a guard or a wing. Somebody who can create his own perimeter shot, like a Kevin Durant or Damian Lillard. Rarely would you ever find a center or a power forward in an isolation set for the game’s final look.

That’s reality for the Sixers, though, who run through Joel Embiid. The team’s MVP candidate had a shot to win Saturday night’s game in regulation, but missed a tough, step-back baseline jumper and the Sixers went on to lose in overtime.

Here’s the play again. They were coming out a timeout, inbounded the ball to Seth Curry, and had him play this entry to Embiid:

Watching that in real time, it seemed like the Sixers wasted a few seconds getting him the ball. Jarrett Allen did a nice job forcing Embiid catch that pass all the way out beyond the three point line.

This is how Joel described the play:

“That was what the defense was giving me. I wanted the last shot and thought if I posted up on the block that they would have tried to get the ball out of my hands, where I have would have to pass and we’d have to scramble around and maybe we would not have gotten a shot (off). But I got the ball in my spot. It doesn’t matter where I caught the ball, I still got to my spot, and that’s the shot I’ve taken 1,000 times. I’ve been making it all season. That’s my shot and I’ve been working on it. It’s unfortunate I missed it. So what? You move on. You learn from it the next time. With another opportunity I’m sure I’m going to make it.”

Only 11 sentences in that quote, but there’s actually quite a bit to parse, so let’s take it a few lines at a time:

“I wanted the last shot and thought if I posted up on the block that they would have tried to get the ball out of my hands, where I have would have to pass and we’d have to scramble around and maybe we would not have gotten a shot (off)” –

This is true, and it illustrates the give and take of where this type of possession should begin. Getting Embiid the ball behind the three-point line with 4.9 seconds on the clock does not seem ideal, but if he catches that ball closer to the basket, then Isaac Okoro (#35) is in a position to dig or double team, and then the ball might come out of Embiid’s hands.

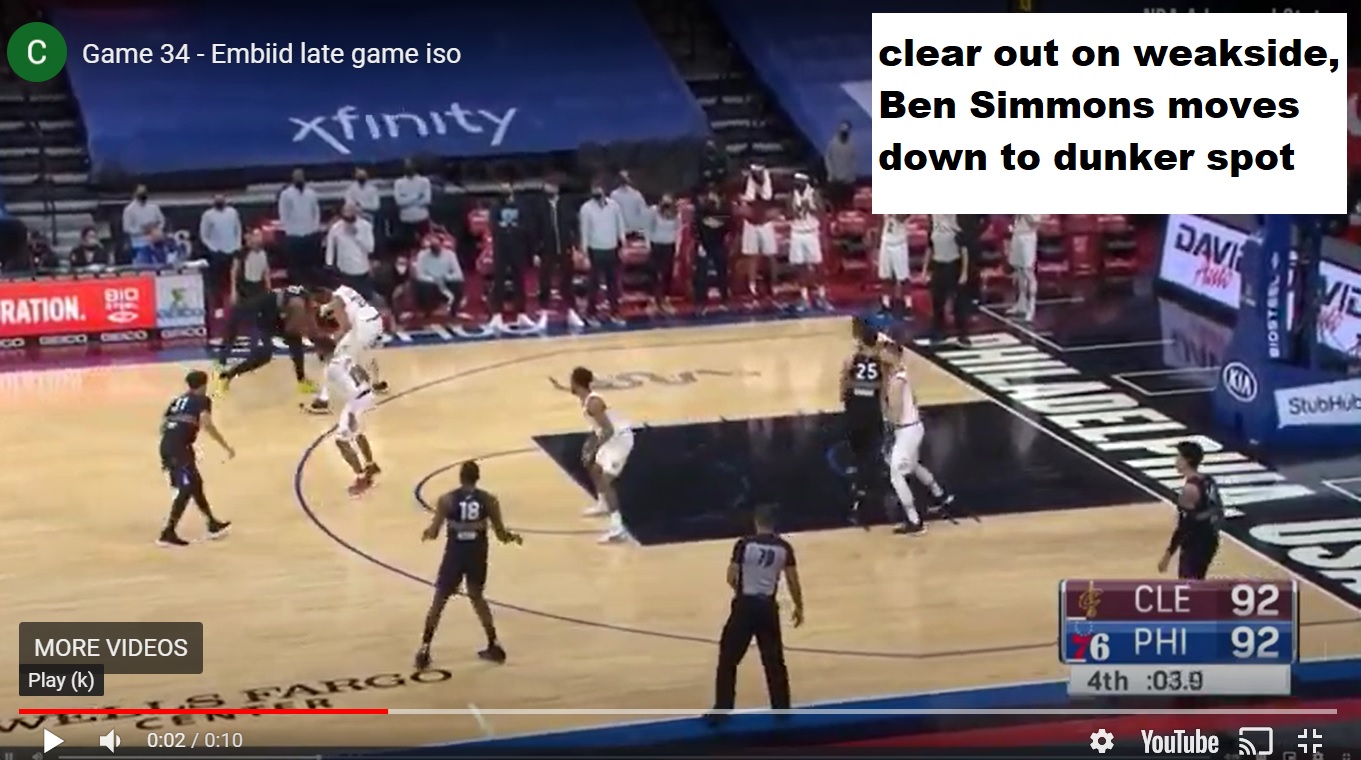

In this case, they throw it to Embiid at the break line, clear out to the weakside, and give him that space to attack instead, which looks like this when you freeze the frame:

Since Ben Simmons is not a shooter, you move him down to the dunker spot and fan out the other three guys. That’s pretty much the way you have to do it if you want to give Embiid that space on the left to attack Allen off the dribble.

“But I got the ball in my spot. It doesn’t matter where I caught the ball, I still got to my spot, and that’s the shot I’ve taken 1,000 times. I’ve been making it all season. That’s my shot and I’ve been working on it.” –

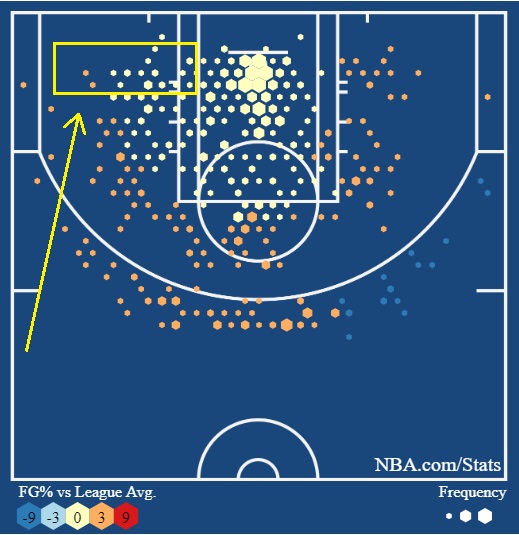

A step-back baseline jumper on an expiring clock is not the easiest shot in the world, but Embiid isn’t off-base with this claim. He has been pretty good from this part of the floor this season, and his shot plot would seem to back that up:

Embiid is pretty much right at the league average from the left baseline. The majority of his face ups and anything in the 10-14 foot range takes place on that side of the floor, too, and you can see how much more frequently he shoots from that side.

Even with a second defender trying to get a hand up to block the shot, it’s a relatively decent look for somebody like Joel.

“It’s unfortunate I missed it. So what? You move on. You learn from it the next time. With another opportunity I’m sure I’m going to make it.” –

The question here really is the viability of iso Embiid as a closer. We’ve talked for a few years now about how the Sixers don’t have that perimeter creator, not since Jimmy Butler. There’s no guy who you throw the ball to and say, ‘go get me a bucket.’

This year, however, Embiid’s game has evolved to the point where he’s able to work from higher catch locations, and Doc Rivers introduced that “delay action” concept, which is when they just throw it to Embiid at the point and let him work. He’s become more than just a post up and face up player and begins at different levels now.

For some context, here’s the data NBA Stats has on Embiid isolation possessions:

- 3.2 possessions per game, 12.1% frequency

- 1.14 points per possession

- 58% shooting

- 85th percentile

Those are good numbers, especially for a big. We think of James Harden as the prime iso guy, and he’s scoring 1.22 points per possession. Kevin Durant is up at 1.25 PPP.

Embiid, however, isn’t far behind, actually tied with Bradley Beal and just slightly pipping Zach LaVine, Zion Williamson, and Paul George. As a center, he has better iso numbers than guys like Jayson Tatum and Kyrie Irving, who log more iso possessions per game. There is efficiency to be found here.

In conclusion, tossing the ball to Embiid at the three-point line actually might not be the worst thing in the world for closing games. In prior scenarios, Rivers has tried multi-action plays where his team cycles through reads, and they’ve been successful with that. As such, I know some fans were frustrated with that call at the end of regulation on Saturday night, but the idea of iso Embiid does seem to come with feasibility and viability.

Kevin has been writing about Philadelphia sports since 2009. He spent seven years in the CBS 3 sports department and started with the Union during the team's 2010 inaugural season. He went to the academic powerhouses of Boyertown High School and West Virginia University. email - k.kinkead@sportradar.com